“Revolution is not a one-time event. It is becoming always vigilant for the smallest opportunity to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses” – Audre Lorde

The term “litigation” can conjure up thoughts of fierce battles in the courtroom, and celebrations or protests on the steps of court buildings. However, these images are only small snapshots of the whole strategic litigation picture.

What is not visible in these snapshots is all the work that happens leading up to and around what happens in the courtroom. In fact, despite their relative invisibility, this is where most of the work takes place.

This blog explores the process we adopt to build strategic litigation campaigns with communities, and why it takes longer than you might think for our cases to get to court. After all, using litigation strategically as a tool for change is a marathon, not a sprint.

“Real change, enduring change, happens one step at a time.” – Ruth Bader Ginsburg

In our “Strategic litigation: a guide for legal action”, we unpack what is meant by “strategic litigation” and what sets it apart from regular legal action.

One of the primary things setting it apart is a holistic litigation strategy. As I have written in an earlier blog, there is no such thing as a single “landmark” case. Litigation campaigns, like other campaigns, are sustained efforts using the law in different ways at different times. That means, before looking at what cases can be built, a strategy needs to be formed.

When Ruth Bader Ginsburg founded the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union, she designed a women’s equality litigation strategy that targeted gender discrimination across policy areas such as the military, tax, social security, and jury service. Instead of pursuing one “landmark” case, this strategy saw her take six cases across a ten-year period and file amicus briefs in many more (if you are unsure what an “amicus” is, you can find a definition in our glossary). A key takeaway from Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s approach is that the strategy must come before a case.

Litigation strategies set out the how, when, where, and why of leveraging the courts to bring about the change needed. It maps out different goals that could be pursued by different types of legal action, across different moments in time. It also establishes how you will target or sequence legal action across this timeline, and how campaigns and other advocacy activities can complement them. Most importantly, it identifies how the strategy can be put into action, what resources are needed, and how potential risks will be navigated. When building a strategy like this, gaps will inevitably arise that will need to be filled: gaps in factual research, gaps in legal knowledge, gaps in relationships with potential allies and partners. Filling these gaps can take time, and is a necessary part of building a robust litigation strategy that can form the basis of any case that will be brought.

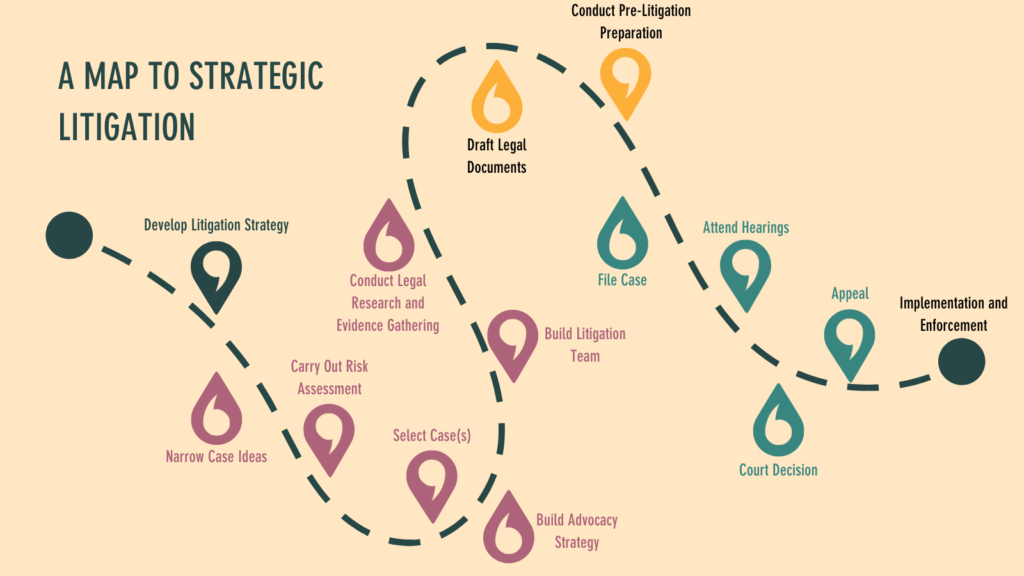

Through this process of designing a litigation strategy, case ideas will surface and will need to be further explored and narrowed. Once a set and sequence of cases has been established that best aligns with and supports the strategy, these cases then need to be “built”. Depending on the case, this process can take time. Legal research will need to be conducted. A process of evidence-gathering will need to be initiated. Movement and team building around a case will need to take place, and further resources will need to be acquired. Furthermore, an advocacy and communications strategy will need to be developed around the case.

All this happens before a case even gets “taken to court”. The formal steps involved in then taking the case to court includes:

-

- Drafting of legal documents: this would include legal arguments, as well as evidence supporting those arguments (such as witness statements);

-

- Filing: this is the submission of the above documents, and this is the formal beginning of a case. After filing, there may be another stage where you must respond in writing to the arguments of the other party to the case;

-

- Hearings: these may not necessarily take place, but in cases where there are public hearings of the case then planning and preparation will need to happen leading up to and during the hearings;

-

- Decision: this will be the decision reached by the court, which is usually provided in writing. There will then be a period of time to appeal this decision to a higher court, which can also mean that the case will have broader impact. If a case is appealed, then the steps will be repeated again;

-

- Enforcement and implementation: this is the work that happens after a positive decision from the court, to ensure that it is maximised for impact.

All these steps in the journey require work and take time, but they also offer many opportunities for capacity building, strategy development, and refining advocacy and campaigning activities. Pursuing litigation in a strategic way is a step-by-step process, and should not be pursued in a “move fast and break things” kind of way. That is why, when we build cases with communities, we are in it for the long haul.

Community-driven strategic litigation

“We have to recognize that there cannot be relationships unless there is commitment, unless there is loyalty, unless there is love, patience, persistence.” – Cornel West

Systemic Justice does not just build strategic litigation, we build strategic litigation in a community-driven way. In other words, we work with a model that places communities in the lead when it comes to the journey outlined above.

As opposed to lawyers (like Ruth Bader Ginsburg) being the strategists and key decision makers driving the strategic litigation process, we want to support communities holding this role in the strategies and cases that concerns them. This is a radical departure from how strategic litigation is usually designed and run in Europe.

We have written before about how we seek to embed Design Justice Principles in our litigation process. These principles shape our approach in various ways, including by:

-

- prioritising the restoring of power to communities during the litigation process;

-

- supporting communities with their strategic thinking, rather than developing strategies for them;

-

- not pushing the legal team’s ideas on what the team thinks communities should litigate on or how;

-

- making the legal process as accessible as possible for community partners; and

-

- helping make litigation a sustainable process for communities.

Doing this work in a truly community-driven way necessitates building strong, long-term, collaborative, and trust-based partnerships with communities. Communities are not merely consulted in our approach, they drive it.

To get communities to a place where they can fully embody this role, we must move at the pace of and adapt to the needs of the communities we work with. Moreover, as a legal team, the first thing we focus on when working with communities is not the law, but rather building a trust-based and sturdy relationship. This is part of the work.

Furthermore, for many of the communities we work with, this is their first exposure to strategic litigation, and sometimes even the law, as a tool in their toolbox. Therefore, as we support communities in designing their own litigation strategies, we also work on building communities’ knowledge and power on litigation and the law. Even where there has been some exposure to the courts or law, the way we work is very different to how communities have worked with or experienced lawyers in the past. This means we might also have to support communities in a process of unlearning and (re)learning when it comes to Systemic Justice’s community-driven approach.

We also recognise that, where cases have been taken with communities in mind, such cases have often, over time, become more and more distant from the communities that will be impacted by them. When building litigation strategies and cases with communities, we also work on developing and implementing a care and support plan for communities. This is to ensure they get the resources, training, support, information, and care needed to fully engage in a sustained way across the litigation process and for the duration of any cases that are brought. Ultimately, we hope that our work with communities can help them build up their strategic litigation capabilities, rather than just help them to “take a single case”.

We are excited to have started on this journey with communities across Europe working on issues of climate justice and social protection and, as cases start to emerge in the strategy design process, we are motivated by the strong, trust-based partnerships that we have forged. We are laying the foundations for “good trouble”, so watch this space.

If you are a community campaigning on racial, social, and economic justice and you are interested in joining us on this type of journey, get in touch!